I’ve mentioned before how I spent a year or so studying Japanese calligraphy and then stopped. Before I stopped, though, I acquired a few skills along with several brushes, paper, weights, felt pads, ink sticks and grind stones.

Most of that gear has either been thrown away, sold or, in the case of the brushes and the ink sticks, passed on to our girls. The only things I’ve kept are a couple seals.

In Asia, for lots of complicated reasons, the preferred method of sealing contracts and official forms is with a literal seal. The seals, known as “chops” in Chinese speaking countries, are called “Hanko” (判子) in Japan. (That’s “Han” as in “Han shot first” and “ko” as in “coke”.)

Every family, mine included, as an official seal for official documents as do most companies. (Actually, I suspect they all do.) The official seals are made by craftsmen and the hanko is officially recorded. As I understand it, every hanko is different, even those made for people with the same last names. Those are usually round and the coolest kids, depending on your point of view, have hanko made from ivory.

Mine are made from soap stone and are the more artistic versions. They were used to sign my calligraphy works (which are buried somewhere and unavailable for reproduction). Because I was in a “this is awesome” philosophical mood, I opted for kanji and then spent time working out a proper pretentious artist’s name.

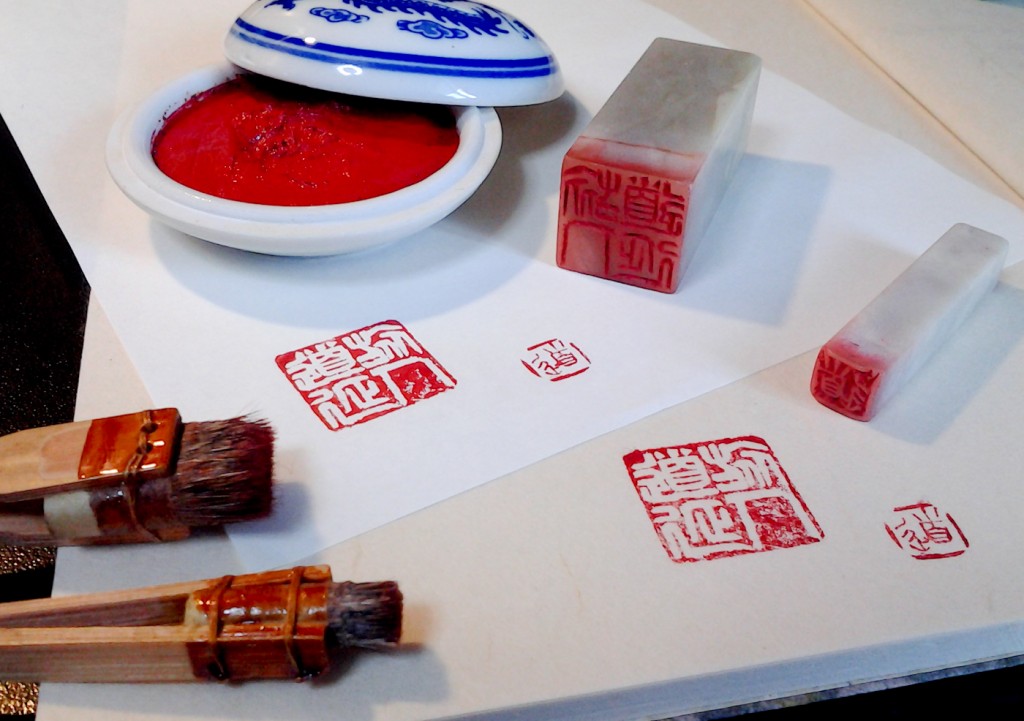

The two hanko and paraphernalia next to the results on Tomoe River paper (top) and Japanese washi (bottom).

The larger version reads 旅人道延, or Tabibito Doen (the latter word is two syllables and pronounced very close to Dwayne). The high concept, which made sense at the time, was that since I was travelling, I’d use the kanji for traveler (旅人) and the letters for road/path (道) and stretches (延). Thus, the traveler’s road stretches (with an implied “into the future”.) This hanko was used on larger works (the paper was about a meter long).

The small version is only the letter “do” (pronounced “doe”) and was used on smaller works.

I don’t remember how much they cost, but I also acquired a couple cleaning brushes and a tub of cinnabar/vermilion paste which is a remarkable concoction of castor oil and vermilion powder and other ingredients that has stayed usable for over 18 years.

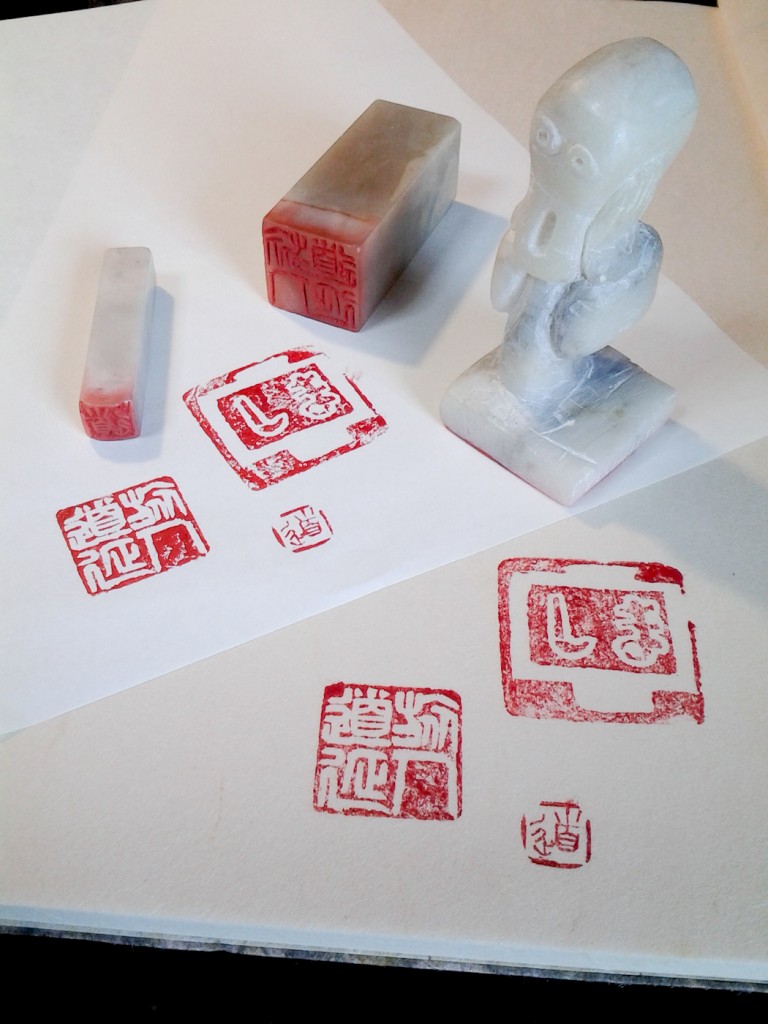

The cinnabar (or vermillion) paste with the ox bone smoothing spatula. Sharp eyes will notice a third stamp.

I was surprised, after a couple do-overs, that the placement of the seals was as important as the calligraphy itself. A perfect work could be ruined by a badly placed stamp or a smudged one.

I use them now to mark the backs of my notebooks. I could make the small one my official stamp, but that would involve paperwork.

I also acquired, as a gift, a hanko hand made by a student. It has his name Nakashima (Naka) 中 and Shima (しま) with the Naka around the outside as a frame. I mostly keep it because he carved it to look like the man in Munch’s “The Scream”.

I’m tempted to have it recarved and turned into my official stamp, but it’s the only reason I remember the student’s name. Instead I’ll keep in on my desk as a way to express my mood.

(Note: If you’re interested in carving your own hanko, you can buy a kit here.)

(Note 2: hanko are also referred to as “inkan” (印鑑). I’ve not been able to tell if there’s a difference as they seem to be used interchangeably.)

Hi, I enjoy your posts and follow daily. It is such a surprise to see your post today, as I finished the process of having my own hanko designed today. It will be carved this week and then shipped. I am very excited, both about using it and having been through the process. Thanks